How much money do Meramec students spend on their appearance

Kelly Glueck

-Managing Editor-

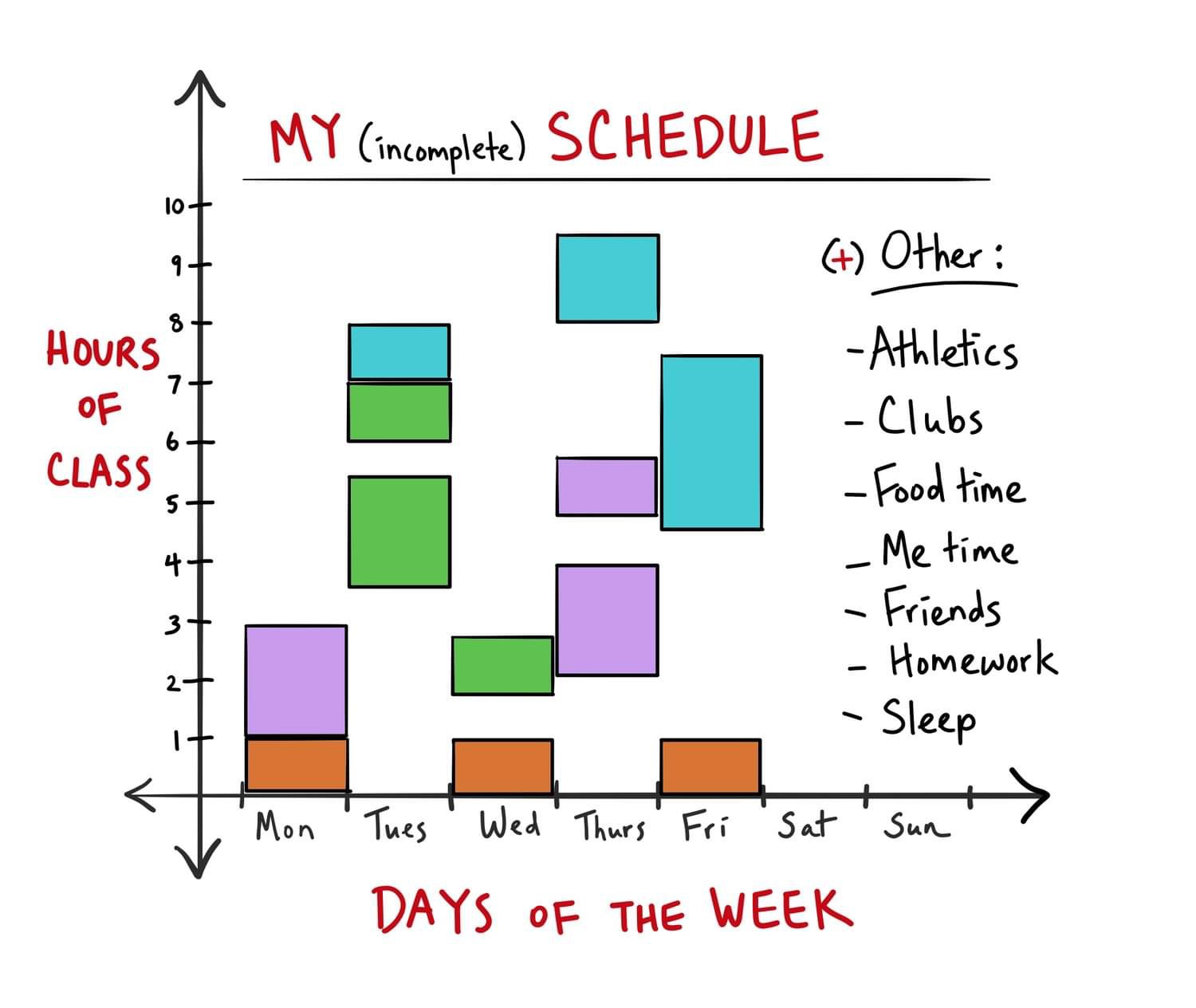

Learn a language, develop an app, become a certified pilot. Cannot find the time? Each of these endeavors take about 336 hours to complete, which is less than the average 400 hours a female STLCC-Meramec student puts toward her appearance each year. While grooming is necessary for our health, what is it about the need to be flawless that wastes so much of our time and money?

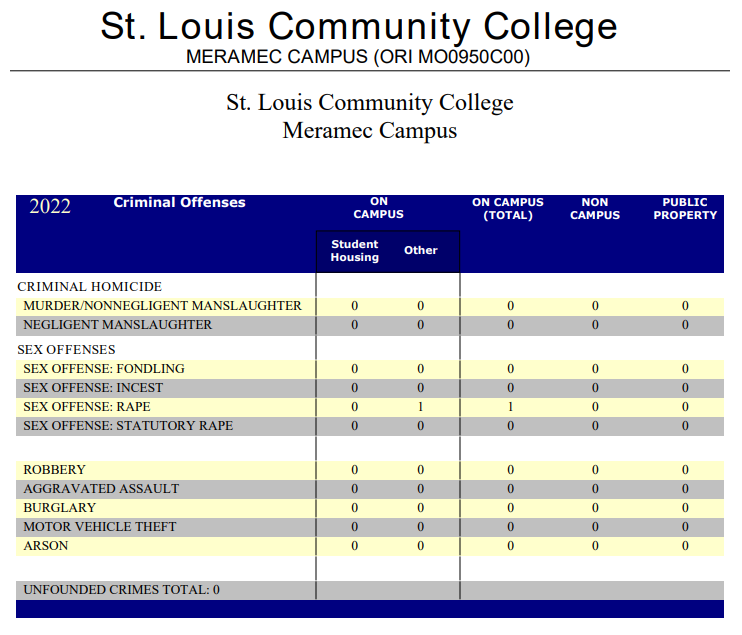

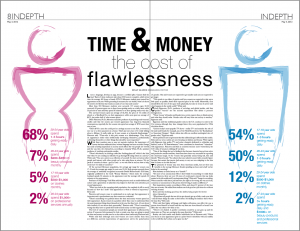

More than 300 Meramec students were surveyed. Of women ages 20-24 surveyed, 68 percent spent one to three hours getting ready on a daily basis; while 50 percent of men said they spend 30 minutes to an hour getting ready every day.

The surveyed women spent an average of $1,403, the price of 16 credits of school or a MacBook Pro, on their appearance; while men spent an average of $673, just under half of what women spend.

Diane Pisacreta, Ph.D., Meramec associate professor of psychology and women’s studies said that the money put toward appearance has long-term financial consequences, especially for the women who spend an average of $730 more than men a year.

“That’s $700 a year she could put in a savings account or an IRA, or toward a new car or a down payment on a home. That’s just one year; we’re really talking about a lifetime. It really adds up. It puts women at a financial disadvantage,” Pisacreta said. “Time-wise it also puts women at a disadvantage. They focus on appearance rather than intellectually developing themselves, professionally cultivating themselves or other things that should be more important.”

While these numbers may or may not surprise students, the importance of beauty has been addressed since written language has been recorded. Image has made a lasting impression on society and it affects the way people are viewed and the way they view themselves, according to Amanda White, Ph.D., assistant professor of sociology and gender studies.

“There’s this theory in sociology called the ‘looking glass self,’ which is the idea that when we are creating our identity we go through life using others as a mirror,” White said. “You use a mirror as a reflection of yourself. So when we look at other people and interact with other people we’re also using them as mirrors. We see parts of ourselves in them – good or bad – so we take that in and use that to help create how we think of ourselves.”

Of the surveyed Meramec population, the average age range for women was 17-19 and the average age range for men was 20-24. Both groups surveyed above the average of nationally recognized economist Daniel Hamermesh’s 2008 data, originally published in the book “Beauty Matters,” which states the average husband spends 32 minutes on his appearance and the average wife spends 44 minutes on her appearance.

Professor of Psychology Vicki Ritts said that pressures such as media-influenced culture and a generation of jobseekers has helped to fuel this extra attention put toward appearance.

“When you look at the emerging adult population, the emphasis is still so much focused on ‘how do I look?’ and appearance is what is valued as important,” Ritts said.

Pisacreta said women come to understand at an early age that appearance is important and a predominant way that women are evaluated.

“There’s something very political about the time and money women spend on their appearance. It puts women in a position where they come to understand that the most important thing about themselves is the way that they look – it’s not about their intellect; it’s not about their personality,” Pisacreta said. “There’s something wrong that they have to spend their hard-earned money on their appearance.”

The level of commitment people put toward their appearance is influenced by society. If someone feels pressured to look a certain way, they are going to spend the time and money to make sure he or she achieves that conformity, Pisacreta said.

White said that although men and women are more similar than they are different, societal expectations of appearance aid in the polarization of gender. She said women are expected to get smaller and men are expected to get larger.

“This speaks to our ideas of gender and how women are expected to take up as little space as possible; that’s their expected piece in the world. Meanwhile, men should fill in the rest of the space both physically, but also in terms of power and what happens in the social world,” White said.

Cindy Epperson, Ph.D., professor of sociology and global studies, said that gender “norms” are the societal expectation that define a person’s biological sex.

“These ‘norms’ tell males and females how society expects them to think and act and what they should value. Gender roles will vary from one society to another,” Epperson said.

Epperson said that traditional gender roles in the U.S. continue to exist in the 21st century, although they have changed since they were popularized in 1950s television shows.

“Look at today’s most popular TV shows – reality TV- and examine the role of the male and female; for example, any of the ‘Real Housewives,’ the ‘Kardashians’ or ‘American Chopper.’ Music videos also offer an excellent sociological view of gender roles,” Epperson said.

All the professors are in agreement that the millennial age is affected by the media. Ritts said our news outlets are now focusing on fashion and beauty. White agrees with Epperson that reality TV and entire channels dedicated to celebrities and fashion, such as “E! Entertainment,” have contributed to Americans’ “obsession” with appearance. Pisacreta said that as countries become more westernized, the U.S.’s idea of beauty is rubbing off on them.

“One of the things that we’re finding is that because America has such an active and productive media machine, Americans have been very successful in exporting the American image. So for women that generally means being tall, thin and blonde,” Pisacreta said. “So cultures that once adored a more fuller, rounder figure because that meant that person had money to eat, are now adapting to the idea that it’s better to be thin and tan.”

The pressures of beauty may stem from American media, but are there any benefits to the average Meramec female spending an hour and a half on her looks in the morning?

Ritts hesitates to claim beauty as a “benefit.’”

“It’s more of an unconscious effort. I don’t think it’s something we really think about. However, there are over 40 years of social psych research that say looks matter in the job world and it’s an important thing,” Ritts said. “Image is everything. When someone walks into a job interview, for right or for wrong, the way you look, conscious or unconscious to the person interviewing, it makes a difference.”

First impressions matter, according to Ritts, and about 67 percent of the time they are accurate. She added that students can look good at a job interview without wearing Armani.

Ritts said that looking good has the ability help people feel better about themselves.

“[Physicians tell people that are sick to get dressed, get up a little, comb your hair – and all those things do make us feel better. It’s finding the balance that’s where the issue lies,” Ritts said.

White said that higher self-image and higher self-esteem can affect the way a person views himself or herself and the way that one views himself or herself can affect the way others view him or her.

“They’re very linked. A positive correlation would be as one goes up and the other goes up. They are moving in the same direction,” White said.

Beauty can both enable and disable individuals but as Piscareta said, “When your focus on your appearance gets to a point where it interferes with your ability to live a full life, that’s when you’ve gone too far.”