The debate is growing louder. Is college really worth it?

Mike Ziegler

-Photo Editor-

The debate is growing louder. Is college really worth it? An ever-increasing higher education cost and a more than 9 percent unemployment rate have more students asking themselves if a degree justifies the cost. The average student with school loans in 2008 graduated college $23,200 in debt according to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education.

An inflated sense of value is perpetuated by the notion that the higher cost of a university, the higher value of an education the student received. This was reported in a 2009 study in the journal, “Research in Higher Education.” The New York Times quoted the authors as saying costs “serve as markers of institutional quality and prestige.”

This year, as University of Missouri Curators debated over raising tuition rates to cover budget gaps, MU Chancellor Brady Deaton said in The Columbia Daily Tribune the problem is Missouri doesn’t charge enough.

Deaton later said he was not advocating excessive tuition costs, just explaining parents have told him their children pass over MU for other schools because they have higher tuition.

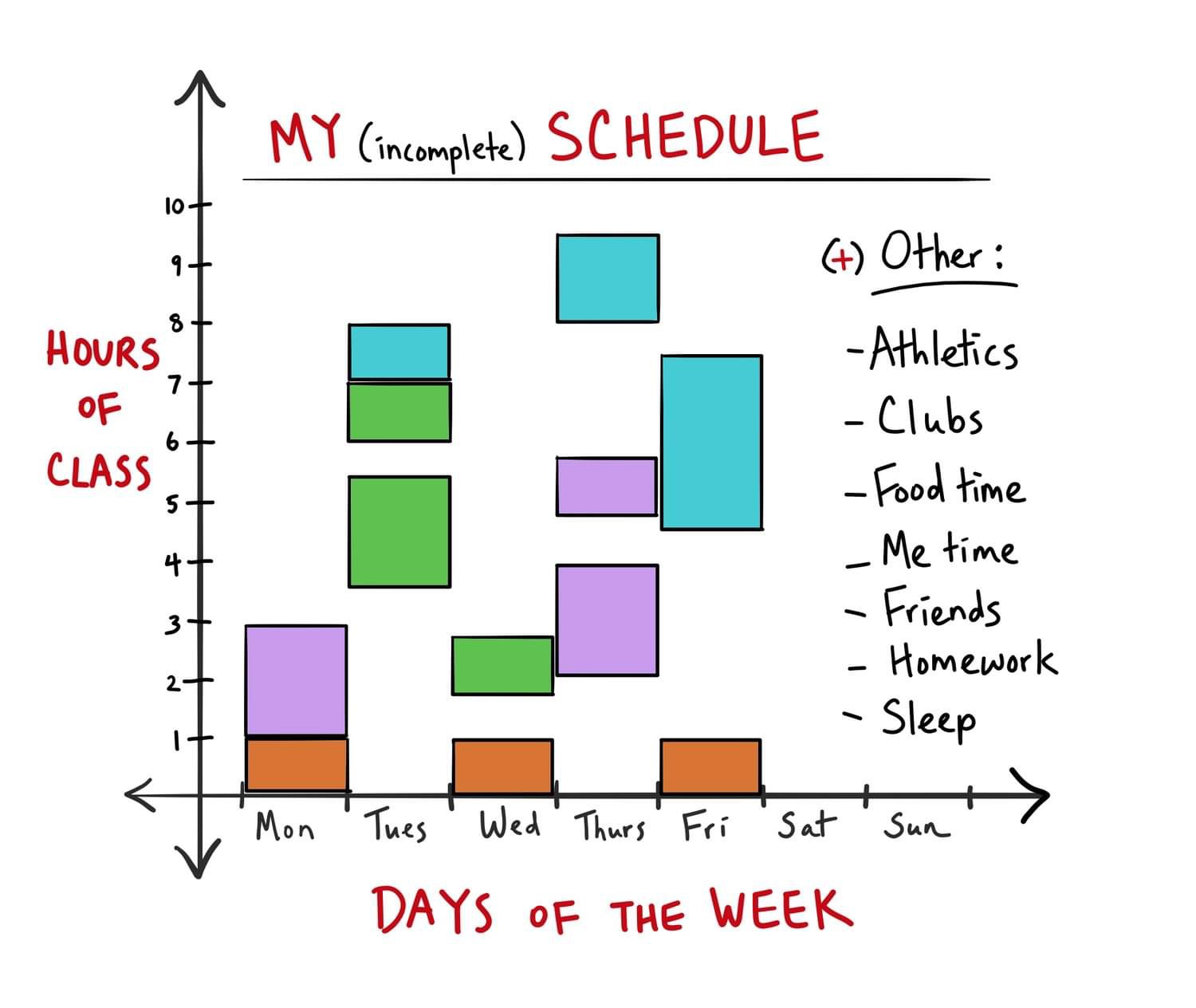

“Often times I think students are overwhelmed by so many options,” Jason Duchinsky, STLCC-Meramec counselor, said. “I think in part what contributes to that saturation is the explicit message go get a degree, and then they’re pursuing degrees that don’t resonate with them as people.”

Yashar Ali, a Los Angeles-based writer and commentator, after applying and not getting accepted to USC, took it as a sign and entered the workforce straight out of high school, choosing the non-traditional route of not going to college.

“I think too much emphasis is placed on what students ‘should’ do rather than what they ‘want’ to do,” Ali said. “It’s the reason so many people live a life that feels unfulfilled.”

The idea of not going to college might make high school administrators cringe in opposition. All public Missouri K-12 school districts are rated on a set of standards through the Missouri School Improvement Program (MSIP).

Among the set of standards measured each year are college and career readiness. One way districts are deemed successful or not in this category is the percentage of students who attend postsecondary education. Additional measures that may be used for reporting purposes on MSIP’s annual report is the percent of high school graduates who not just attend a postsecondary institution, but graduate with an associate or bachelor’s degree.

“How do we define success or productivity?” Duchinsky said. “High schools want to be able to say this percentage of our graduates went on to college and this percentage graduated from college. It means something, but really does it mean what we think that it means or what everyone appears to agree with what it means?”

If the state concludes a district isn’t performing adequately according to the overall set of standards measured each year, the consequences could include losing their accreditation and the State board of Education coming in and assuming control of the district.

What is a high school senior to do other than college after high school? Take some time off from school. That is the message from Duchinsky.

“I would be an advocate to not abandon the pursuit of higher education,” Duchinsky said. “I would encourage a moratorium on pursuing that upon the graduation of high school, like a minimum three years maybe even five years, so that someone can go out and gain some life experience or some work experience.”

European students are typically encouraged to have what is called a gap-year upon graduating high school and attending college. The idea is to take a year off to work, volunteer and have a better idea of real world challenges.

The transfer of the gap-year practice and mentality from European culture to the U.S. has yet to become wide spread.

“Making it more of a societal and cultural practice whereby people literally don’t go to school for a period of time, they go and do service, it’s teaching, it’s making a concerted effort so people can figure these things out,” Duchinsky said.

Not going to college should not be taken as the easy or lazy way out of putting the work towards a career, Yashar said.

“Skipping college does not mean you should drink the night away and then sleep until 2 p.m.,” Ali said. “It’s only if you have a drive to succeed on your own that you should consider not going to college.”

Both Ali and Duchinsky say the benefits of higher education cannot be dismissed.

“You can discover how to think, and how to critically think. We have to be able to present logical arguments, to question appropriately, not to serve reactivity, to understand, make corrections and move forward,” Duchinsky said. “Otherwise we’re just stuck in the rut of rigidity.”

Students who are anxious about what they want to do in their life may feel like their time in school or at Meramec is a waste of time. Duchinsky said to think otherwise.

“If you’re here and you’re earning C’s, you’re earning college credit,” Duchinsky said. “You’re not wasting your time. It may feel like that experientially, that makes sense to me because you really haven’t found that thing that works for you. You haven’t found that fit, that thing you want to cultivate.”

A hesitation many students or parents and teachers come across when choosing or advocating to take time off from school

is they will make that step to

attend a postsecondary institution.

“A common fear when students pose that question is they don’t want to follow through and take some time because they think they are never going to come back,” Duchinsky said. “It could be really a strong statement on where they’re at in their relationship with education.”

Duchinsky said they need to deal with the possibility of not coming back.